Predatory Journals: How to Avoid the Dark Side of Academic Publishing

If you are a student, you may have received a random email inviting you to submit an article to a journal you’ve never heard of. Or to publish your thesis as a book with a publisher whose name sounds legit, but curiously you’ve never read a book from. If you are a researcher, you may have gotten tired of deleting badly written emails inviting you to be the editor of a new journal whose title sounds all too important but has nothing to do with your work. What’s all this and what are some simple steps for novices to avoid falling in the trap? Francesc Baró explains.

Limits to growth, please

The first modern academic journal, the French Le Journal des Scavans, was published in 1665. Since then, and especially in the second half of the twentieth century, the number of journals (as pretty much everything else) has grown exponentially. As of 2015, there are a total of – take a breath - 36,442 (!) active journals.

In the last years, there has been a proliferation of open access journals. This is good. Knowledge should be open to everyone, free of cost. Private publishers such as Elsevier profit from the unpaid labour of authors and reviewers. They then charge Universities and anybody that wants to access articles exorbitant prices.

What about all those open access journals though, who unlike Plos One, have not built a reputation for themselves? How can you tell a trustworthy from a bogus journal? In many open access journals, you have to pay to publish. This has created a new problem – the proliferation of fraudulent or so-called predatory journals.

Show me a predator

As a good scientist, let me start with a definition - from the usual source we scientists use: Wikipedia. Predatory publishing is “an exploitative academic publishing business model that involves charging publication fees to authors without providing the editorial and publishing services associated with legitimate journals (open access or not)”.

It was this smiley looking chap, librarian and researcher Jeffrey Beall, who first coined the term. Authors are tricked like preys, Beall argued, mislead by bogus publishers into publishing with them. Beall established comprehensive criteria for spotting predatory publishers and published the first list of (potential, possible, or probable) predatory publishers. He had though to take the list offline in January of last year, when Frontiers Media, an open access publisher included on the list, opened a misconduct case against him.

Fortunately, the list was replicated and continues to be updated anonymously.

Here are some of Beall’s criteria for classifying a publisher as predatory:

- The publisher's owner is identified as the editor of each and every journal published by the organization.

- Two or more journals have the same editorial board.

- The publisher demonstrates a lack of transparency in publishing operations.

- The publisher provides insufficient information or hides information about author fees, offers to publish an author's paper and later sends an unanticipated "surprise" invoice.

- The name of a journal is incongruent with the journal's mission.

- The publisher dedicates insufficient resources to preventing and eliminating author misconduct, to the extent that the journal or journals suffer from repeated cases of plagiarism, self-plagiarism, image manipulation, and the like.

Where are the preys and why is predatory publishing a big problem?

Most articles published in predatory journals come from authors living in India; however, this is not a problem restricted only to developing countries. More than half of the papers submitted to predatory journals came from authors from higher-income countries, with the United States ranking in second place after India. Researchers from countries like Japan, Italy and the UK were also found to publish in substantial numbers in predatory journals.

Predatory journals are not a problem only because you pay someone who does a bad job, but because they propagate bad science. Predatory journals are much more likely to accept a fake editor, such as Dr Anna O. Szust (Dr ‘Fraud’ in Polish). They are also more likely to accept a flawed paper submitted by a fake scientist.

Think. Check. Submit

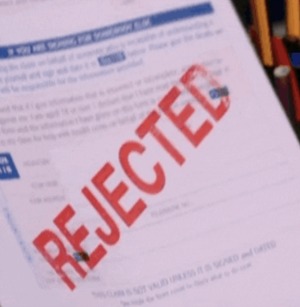

If you are a young researcher applying for a job, you don't want to be caught with a predatory publication on your CV.

How do you choose a journal then for your paper? If you are a student, ask your supervisor. If your supervisor is not that present and can’t help you, then that’s a good sign you should change supervisor  .

In the meantime, use common sense - always think and check before you submit.

.

In the meantime, use common sense - always think and check before you submit.

Think: can you trust the journal or do you need more information before deciding whether to submit there? (You trust a journal if you know the name and if people from your field publish there).

Check: have you read, or would you read, articles from this journal? Do you know the organization who publishes the journal? Can you contact the journal easily if you need to? Are they clear about their publication fees? If you sent a paper, did it follow a peer-review, and were the reviews well-written and relevant to your topic? Do you know the names or reputation of members of the editorial board? Are articles from the journal indexed in any of the services that you use (Web of Science, Scopus, etc.)?

No one is too old to think

Senior researchers: you also need to think and check as well, please. Adding your name and the name of your institutions to the editorial boards of bogus journals makes it hard for young students to tell good from bad journals. If the new ‘Journal of International Science’ that you’ve never heard of contacts you for an honorary position on its editorial board, don’t think ‘why not?’, and proceed to add it to your CV. Check who is running the journal. Ask other colleagues about it. Check who else is on the board, and ask the publisher about their peer-reviewing standards. Notice your communication and how the publisher responds. Is this someone who is serious about a new open access project, or someone who only wants to do a quick and dirty job?

If it is not a serious publication – hit the spam button and move on with your day.

Do you have any additional tips for avoiding predatory journals? Leave your comments below!